I STOOD ON the balcony of the school block and surveyed the campus of the Anglo-Chinese School at Barker Road. I had not been back there since I graduated some four decades ago (I was accompanying Shaw Hur to buy his textbooks during the year-end break as he prepared for secondary school).

I searched for a familiar landmark – any familiar landmark – of the place I had spent ten years of my school life. I couldn’t. Every inch of the grounds had been razed and, in its place, new buildings erected.

Gone were the open spaces and lawns (more like sandy patches from our constant trampling) that afforded students the space to play before and in between classes. And play we did: football, marbles, spider-catching, chatek, kuti-kuti, hantam bola… We invented our own games and laid down our own rules. We found our own fun – lots of it. And when you sat quietly in the afternoons, you could hear the crickets chirp.

My mind returned to the present and it dawned on me how much the multi-storey buildings, squished up against one another, resembled the HDB jungle. The school field, where many a scrape and bruise was inflicted, was missing, replaced by a carpark that shouldered a swimming pool above. A boarding school for foreign students was even jammed into the premises. Every square foot of real estate was manicured, exquisitely engineered for maximum capacity.

What does all this do for (or to) students? Sure, the AV equipment was state of the art, the auditorium outfitted with cinema-like plushness, and the driveways pristinely landscaped. But how does the environment facilitate play? How do students find their own leisure? Where do they go to do that? Yes they are studying, but are they learning?

If all this sounds depressingly familiar, that’s because the campus reminds us of the country itself. The island is blanketed with residential blocks built ever closer and stacked up ever higher. It teems with inhabitants, the number of which this city has never seen.

But fast as it was, construction on the island was always one step behind a burgeoning population whose explosive growth, ignited by lax immigration laws, meant that the infrastructure would be overtaxed.

With the mass influx of foreigners came the escalation of the cost of living. At the same time, wages for the locals were put under downward pressure. Retrenchments and unemployment have risen. Leisure has become a scarcity and where there was once spacious greenery, there is now only bodies and concrete. Stress and work-related psychological disorders, as one might expect, run high. For the average Singaporean, the quality of life has deteriorated.

That wasn’t all. The school’s wholesale makeover also meant that there was little I could relate to my son. There was nothing to share with him about how I grew up in a place in which he was now going to grow up. The past-present dislocation was as rude as it was complete.

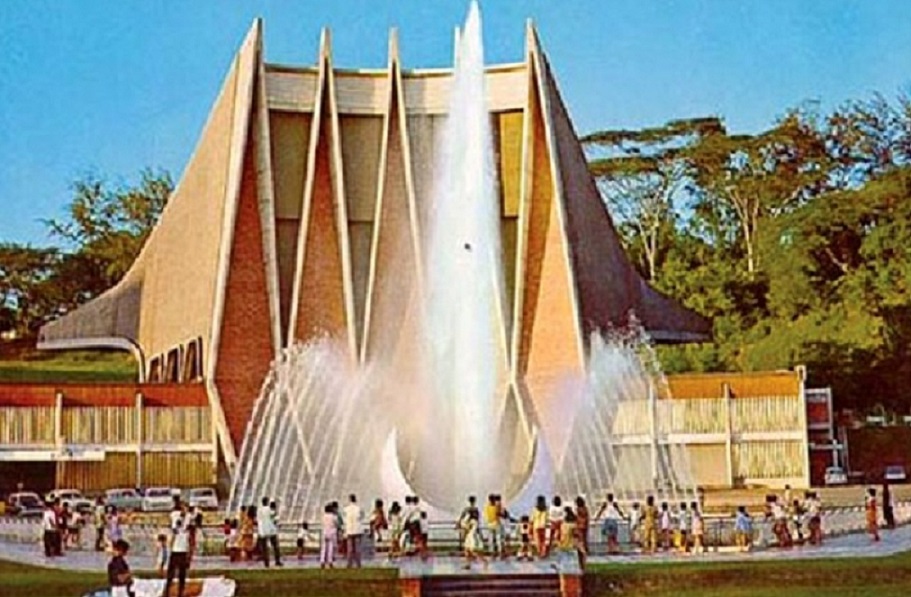

Again, the situation is evocative of present-day Singapore. Anything and everything that served to remind us of days gone by – the National Theatre (photo above), Bugis Street, Satay Club, the National Library, Kallang Park – have been demolished and replaced by shopping centres, expressways and golf courses.

When the break between past and present is so abrupt and comprehensive, we become unmoored from our own history. What, then, binds us to our roots? Need it be said that an undeveloped sense of belonging erodes our national identity?

But can this country, one may be tempted to ask, afford to indulge in idle reminiscence? Why hanker for a past that would have impeded economic progress?

These are wrong questions to ask. Progress and the retention of our collective past don’t have to be mutually exclusive; national development can proceed even as we preserve our history. What is needed to achieve a seemly balance are enlightened and dedicated planners. Japan and Europe, to cite but two examples, have done admirably in pushing the boundaries of modernisation while retaining their proud traditions and heritage.

If we insist on hanging a price-tag on everything, as this country’s officialdom is wont to do, then what value do we put on places that tell the story of where we came from or where we’ve been? What amount of money do we place on Singaporeans emigrating because they don’t know what being Singaporean is anymore? What price do we figure for citizens living disengaged lives, tethered together only by that national creed that ‘No one owes us a living’ or its variant ‘What’s in it for me’?

Even if we accept that nostalgic sentimentality has no place in the kind of hard-nosed pragmatic thinking needed for economc success, it is entirely appropriate to question what all the upheaval and change has brought us. A more genteel and less stressful lifestyle? A sustainable economic structure that ensures financial security for our retirees? A future that promises hope and opportunity for our youth? A system that can still deliver the Singapore Dream for our workers?

When we cast our eyes ahead and see only ominous clouds, what conjures even more disquiet is to look behind and see that we’ve been cut adrift.

Source: www.cheesoonjuan.com