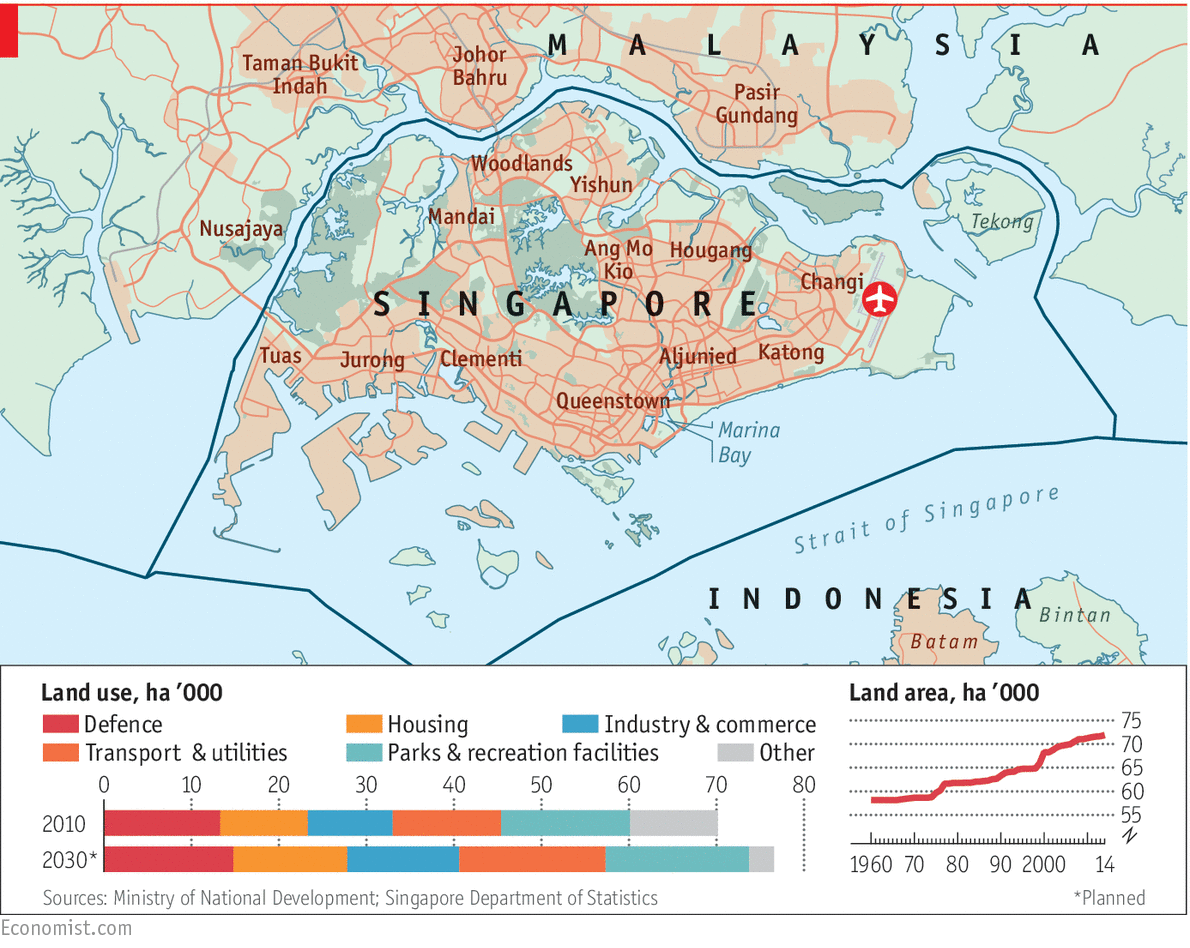

AT 50, ACCORDING to George Orwell, everyone has the face he deserves. Singapore, which on August 9th marks its 50th anniversary as an independent country, can be proud of its youthful vigour. The view from the infinity pool on the roof of Marina Bay Sands, a three-towered hotel, casino and convention centre, is futuristic. A forest of skyscrapers glints in the sunlight, temples to globalisation bearing the names of some of its prophets—HSBC, UBS, Allianz, Citi. They tower over busy streets where, mostly, traffic flows smoothly. Below is the Marina Barrage, keeping the sea out of a reservoir built at the end of the Singapore River, which winds its way through what is left of the old colonial city centre. Into the distance stretch clusters of high-rise blocks, where most Singaporeans live. The sea teems with tankers, ferries and container ships. To the west is one of Asia’s busiest container ports and a huge refinery and petrochemical complex; on Singapore’s eastern tip, perhaps the world’s most efficient airport. But the vista remains surprisingly green. The government’s boast of making this “a city in a garden” does not seem so fanciful.

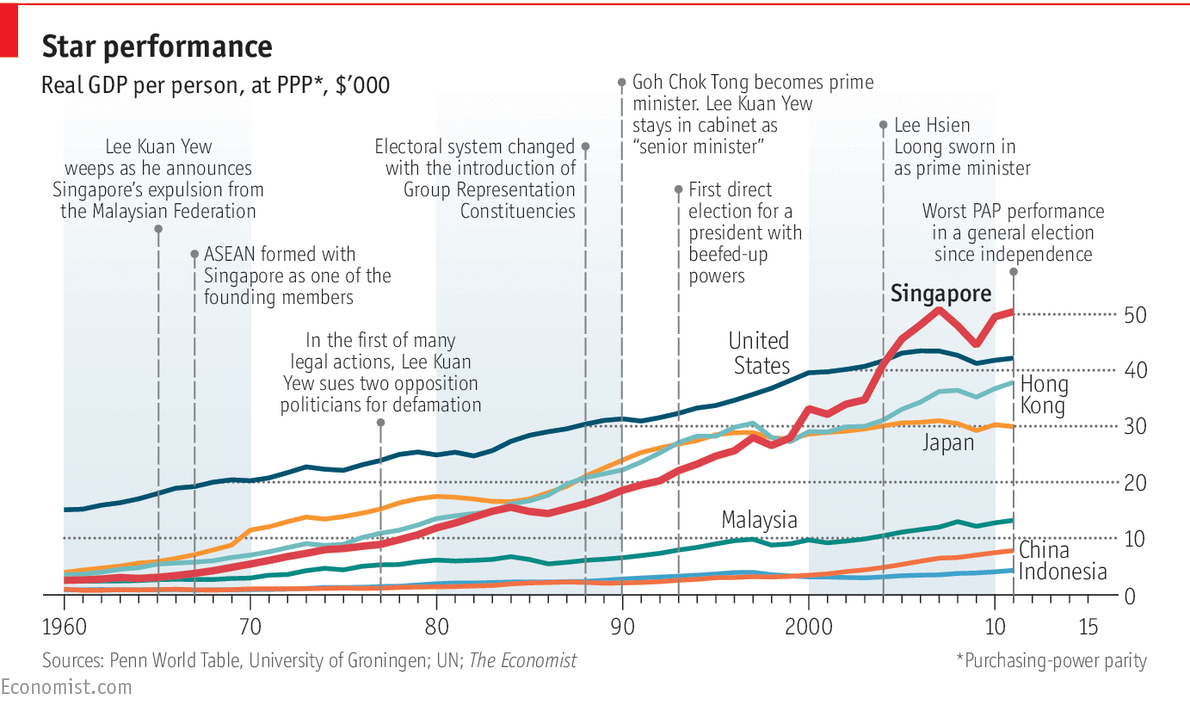

Singapore is, to use a word its leaders favour, an “exceptional” place: the world’s only fully functioning city-state; a truly global hub for commerce, finance, shipping and travel; and the only one among the world’s richest countries never to have changed its ruling party. At a May Day rally this year, its prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, asserted that “to survive you have to be exceptional.” This special report will examine different aspects of Singaporean exceptionalism and ask whether its survival really is under threat. It will argue that Singapore is well placed to thrive, but that in its second half-century it will face threats very different from those it confronted at its unplanned, accidental birth 50 years ago. They will require very different responses. The biggest danger Singapore faces may be complacency—the belief that policies that have proved so successful for so long can help it negotiate a new world.

In 1965 Singapore was forced to leave a short-lived federation with Malaysia, the country to its north, to which it is joined by a causeway and a bridge. Lee Kuan Yew, Lee Hsien Loong’s father, who became Singapore’s prime minister on its winning self-government from Britain in 1959, had always seen its future as part of Malaysia, leading his country into a federation with its neighbour in 1963. He had to lead it out again when Singapore was expelled in 1965. By then he had become convinced that Chinese-majority Singapore would always be at a disadvantage in a Malay-dominated polity.

Mr Lee’s death in March this year, aged 91, drew tributes from around the world. But Mr Lee would have been prouder of the reaction in Singapore itself. Tens of thousands queued for hours in sultry heat or pouring rain to file past his casket in tribute. The turnout hinted at another miracle: that Singapore, a country that was never meant to be, made up of racially diverse immigrants—a Chinese majority (about 74%) with substantial minorities of Malays (13%) and Indians (9%)—had acquired a national identity. The crowds were not just mourning Mr Lee; they were celebrating an improbable patriotism.

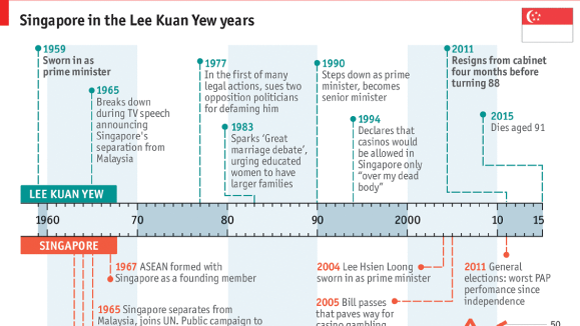

Lee Kuan Yew himself defined the Singapore exception. As prime minister until 1990, he built a political system in his image. In line with his maxim that “poetry is a luxury we cannot afford,” it was ruthlessly pragmatic, enabling him to rule almost as a (mostly) benevolent dictator. The colonial-era Internal Security Act helped crush opposition from the 1960s on. Parliament has been more of an echo-chamber than a check on executive power. No opposition candidate won a seat until 1981. The domestic press toes the government line; defamation suits have intimidated and sometimes bankrupted opposition politicians and hit the bottom line of the foreign press (including The Economist).

Singapore, it is sometimes joked, is “Asia-lite”, at the geographical heart of the continent but without the chaos, the dirt, the undrinkable tap water and the gridlocked traffic. It has also been a “democracy-lite”, with all the forms of democratic competition but shorn of the unruly hubbub—and without the substance. Part of the “Singapore exception” is a system of one-party rule legitimised at the polls and, 56 years after Mr Lee’s People’s Action Party (PAP) took power, facing little immediate threat of losing it. The system has many defenders at home and abroad. Singapore has very little crime and virtually no official corruption. It ranks towards the top on most “human-development” indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality and income per person. Its leaders hold themselves to high standards. But it is debatable whether the system Mr Lee built can survive in its present form.

It faces two separate challenges. One is the lack of checks and balances in the shape of a strong political opposition. Under the influence of the incorruptible Lees and their colleagues, government remains clean, efficient and imaginative; but to ensure it stays that way, substantive democracy may be the best hope. Second, confidence in the PAP, as the most recent election in 2011 showed, has waned somewhat. The party has been damaged by two of its own successes. One is in education, where its much-admired schools, colleges and universities have produced a generation of highly educated, comfortably off global citizens who do not have much tolerance for the PAP’s mother-knows-best style of governance. In a jubilant annual rally to campaign for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights on June 13th, a crowd estimated at 28,000 showed its amused contempt for the illiberal social conservatism the PAP has enforced. Younger Singaporeans also chafe at censorship and are no longer so scared of the consequences of opposing the PAP.

The PAP’s second success that has turned against it is a big rise in life expectancy, now among the world’s longest. This has swelled the numbers of the elderly, some of whom now feel that the PAP has broken a central promise it had made to them: that in return for being obliged to save a large part of their earnings, they would enjoy a carefree retirement. And it is not just old people who have begun to question PAP policies. Many Singaporeans are uncomfortable with a rapid influx of immigrants. These worries point to Singapore’s two biggest, and linked, problems: a shortage of space and a rapidly ageing population.

Source: www.economist.com